By the middle of the eleventh century, Earl Godwine might have seemed

pretty much at the height of his power. His daughter was married to

King Edward, Godwine himself held the most important Earldom in England

and his second son Harold was Earl of East Anglia. He had more

strapping sons awaiting their turn for the next vacant earldoms.

But on closer inspection, things were not quite right. By 1051, it

was apparent that Queen Edith was not likely to give birth to an heir,

thus reducing her own and Godwine’s influence. Swegn,

Godwine’s eldest son, had shamed the family by his outrageous behavior,

then committed the heinous crime of murdering his own cousin. And to

make matters worse, King Edward was surrounding himself with powerful

Norman allies and churchmen, culminating in appointing Robert of

Jumieges as Archbishop of Canterbury against Godwine’s and the local

monks’ approved choice. Archbishop Robert immediately began poisoning

Edward’s mind against Godwine, especially bringing up the old question

about Alfred‘s fate and Godwine’s alleged role in the tragedy concerning the King’s brother.

Things came to a head when Eustace, Count of Boulogne, visited King

Edward in September, 1051. On his return trip, he and his men attempted

to force the residents of Dover to give them lodging in their homes,

just as they were used to in their native country. The stout Dover

townsmen resisted, one was killed in his home, a Frenchman was killed in

return, and the intruders mounted their steeds and plunged through the

town, slashing and maiming whoever got in their way. The townspeople

resisted, turning the incident into a full-fledged skirmish, and when

all was done twenty English and nineteen Frenchmen lay dead on the

streets.

Eustace turned around at full gallop and took his remaining men back

to King Edward at Gloucester, demanding justice. Enraged, the King

summoned Earl Godwine and insisted that he immediately chastise the

offending town with fire and sword. This was putting the king above the

law, and Godwine refused, insisting on a full trial. Then, having had

his say, he retreated to his estate, leaving the King securely in the

hands of the Normans. It didn’t take long before Godwine’s refusal to

obey the King was construed as traitorous.

One thing led to another, and by the end of the month the tide was

turning against Godwine. Edward summoned the other great earls of the

land to support him against Godwine’s family; ultimately the

King commanded Godwine and Harold to appear and answer charges. Godwine

only agreed to do so if the King issued a safe-conduct. Edward

refused.

Godwine knew there was no hope for his cause, at least for the

moment. He had apparently been preparing for such an eventuality,

because much of his treasure had already been loaded on a ship, and he

quickly left the country along with most of his family. Their

destination was Flanders, a common refuge for English exiles and home

Count Baldwin, brother of Tostig’s new bride. On a different ship,

Harold and his younger brother Leofwine took sail for Ireland, where

they were well-received by Dermot, King of Dublin and Leinster.

Poor Queen Edith, caught between father and husband, was quickly

trundled off to a convent and deprived of all her goods, real and

personal. Did Edward think this was going to be permanent? Elated at

his successful coup, apparently he wanted to make the most of it. But

his freedom from Godwine was destined not to last.

Saturday, July 18, 2015

Monday, June 22, 2015

The almost forgotten Edith of Wessex, Queen of England

Edith was a common name in Anglo-Saxon England, and it’s hard to keep them all straight. You are more likely to see this name spelled Ealdgyth, Editha, Aldgyth, Eddeva, Aldyth, Eadgyth, Edyth…I’m sure I missed a few. I like to think of her as Edith Godwindottir, but she is rarely found under that name. Why Edith of Wessex? She was Queen of England, not Wessex. She did not belong to the House of Wessex like her husband Edward the Confessor. Since her father was first Earl of Wessex, I suppose that is why the name stuck, though I do find it puzzling.

I also find it ironic that one our primary sources of the period, the Life of King Edward who rests at Westminster was commissioned by Edith herself (admittedly called a work of propaganda), and yet she’s been largely overlooked in favor of her illustrious brother Harold II. Try finding any artwork about her; oh yes, there is one memorable depiction of Edith warming Edward’s feet on his deathbed in the Bayeux Tapestry. If you look really hard you can see a female figure. There’s another depiction of her in a MS illum. next to her husband. But that’s about it. Nonetheless, according to Wikipedia, at the time of her husband’s death she was the wealthiest woman in England and the fourth wealthiest person in England after the King, Archbishop Stigand, and her brother Harold. Of course, by the time William was through with her, I imagine some of that great wealth had dissipated.

As was natural for a noble-born daughter, Edith didn’t have any say in her marriage plans. She was a very important pawn in her father’s ambitions, and I imagine Godwine didn’t even consider that she would object to becoming queen of England. But King Edward was at least 20 years older than her, and it seems to be common knowledge that he wasn’t terribly friendly toward her father. It’s pretty clear that Edward held Godwine responsible for the violent death of his brother Alfred, no matter how much the Earl protested his innocence. I wonder who was more unwilling: the bride or the groom?

So what kind of marriage did Edward and Edith have? It is thought by some that Edith commissioned Edward’s Life as an attempt to save face concerning her barren marriage. After all, a woman was always held responsible for a lack of children, and England’s fate relied on her. If she could portray Edward as too saintly to be anything but celibate, then she was off the hook. Was this really the case? Or did Edward find her guilt-by-association too much to overcome? Did they ever consummate the marriage? Or was one of them merely infertile? Hmm, one of the great mysteries of the eleventh century.

One thing is for sure: once Earl Godwine was sent into exile in 1051, poor Edith was trundled off to a nunnery at the earliest opportunity. It is said that if Archbishop Robert of Jumieges had his way, Edward would have annulled his marriage. But the King stopped short of this; perhaps he feared the consequences. On Godwine’s return, Edith was reinstalled as well, and for the rest of his reign she was treated with respect. On his deathbed, Edward said she had always been like a loving and dutiful daughter. Of course, those could have been her propagandist’s words, but they do put some distance between man and wife.

Edith does seem to have a reputation as a well-educated woman, speaking many languages; she made sure Edward’s appearance was always exquisite, outfitting him with fine accessories and jewels. She is also thought to be demanding and possibly ruthless; there was an assassination at the Christmas Court in 1064 which has been pinned on Edith, who allegedly ordered the murder of a certain Gospatric as a favor to Tostig, her closest brother. It must have been difficult for her to be sidelined after Edward died, but in those challenging times maybe it wasn’t such a bad thing to fade into the background. At first Harold treated her as befit her station, then after the conquest William pretty much left her alone, provided she didn’t make any trouble for him. William even buried her in Westminster Abbey beside her husband. In the end it could be said that she fared better than her more illustrious siblings.

Friday, June 19, 2015

Who is Harthacnut?

And so Canute and Emma’s child Harthacnut was born in 1017. It seems ironic to me that the young heir Harthacnut was sent to Denmark when he was eight years old, under the regency of Canute’s brother-in-law Jarl Ulf, to help strengthen Canute’s hold on the country. Why would England’s heir be raised in Denmark? But that’s how it went, and in Denmark he stayed, eventually ruling in his own right. When Canute died unexpectedly in 1035, his firstborn son Harold Harefoot was resident in England, and heir Harthacnut had his hands full in Denmark and did not dare leave the country.

The matter went before the Witan. Earl Godwine and Wessex were in favor of Harthacnut, and the North favored Harold, their native son. The Witan ruled, at least short-term, to divide the country and appoint Harthacnut King in the south, and Harold King north of the Thames. Apparently Emma acted as regent, and sent her son increasingly insistent messages to come and claim his kingdom.

Unfortunately, Harthacnut could not get away, and by 1037 Harold Harefoot claimed the whole kingdom, causing Emma to flee to Bruges in Flanders. There she awaited the arrival of Harthacnut who sailed to join her in 1039 with 10 ships, preparing to invade England. As it turned out, the invasion was not necessary because they heard word that Harold was ailing. Indeed, the king died a few months later, and Harthacnut sailed to England with 62 warships to claim his kingdom.

Actually, the transition was peaceful and Harthacnut raised a Danegeld of 21,000 pounds to pay them off, just like Canute had done in 1017. The first thing he did on taking the throne was to order the body of his brother, Harold Harefoot, disinterred and thrown into the Thames. That certainly set the stage for his short reign! Harthacnut ruled by intimidation, harrying the population when they objected to his harsh taxation to pay for a large fleet necessary to keep things under control.

Harthacnut had health problems of his own; in 1041 he invited his half-brother Edward (the Confessor) to live in England, and may have made Edward his heir. And not too soon! In June of 1042, during a wedding feast as he was toasting the bride, Harthacnut went into convulsions and died shortly thereafter, unmourned by all but his mother.

Hence ended the brief reign of the Danes. If Svegn Forkbeard, Canute and his sons weren’t so short-lived, things might have turned out differently for Anglo-Saxon England.

Sunday, March 15, 2015

Did Harold die from an Arrow in the Eye?

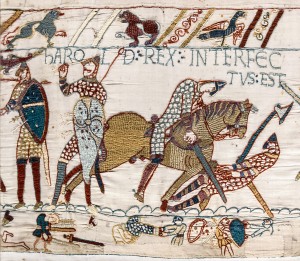

The

Bayeux Tapestry gave us an iconic image of Harold pulling an arrow from

his eye. It must be Harold: the name is embroidered around his head and

spear. And since the Tapestry is created so close in time to the actual

event, it is considered on of the major sources of documentation and

hence to be trusted. But somehow, even the identification of the wounded

hero is questioned by some, and further investigation raises more

questions than it answers. Why?

The

Bayeux Tapestry gave us an iconic image of Harold pulling an arrow from

his eye. It must be Harold: the name is embroidered around his head and

spear. And since the Tapestry is created so close in time to the actual

event, it is considered on of the major sources of documentation and

hence to be trusted. But somehow, even the identification of the wounded

hero is questioned by some, and further investigation raises more

questions than it answers. Why?Well, one thread of discussion is the identity of the figure at Harold's right, falling to the ground in the process of getting his leg cut off. As we learned from the 11th century Carmen de Hastingae Proelio, Harold was hacked up by four attackers (one of them might have been William). From 12th century Wace we learned that Harold was wounded in his eye by an arrow, then felled while still fighting, struck "on the thick of his thigh, down to the bone". So many historians think the second figure is Harold. A third opinion is that both figures are Harold, since the Tapestry could be read like a long cartoon, where one scene leads to the next.

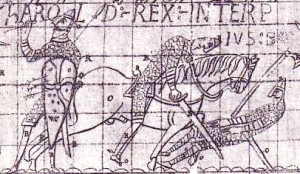

I

recently learned about evidence that gives credence to the third

theory, but only a close-up view will enlighten: a row of holes next to

the second figure's eye, that looks suspiciously like stitches that have

been removed! An arrow? If so, then clearly this is the same figure as the other. As historian David Bernstein tells us in a thoroughly investigated "The Blinding of Harold and the Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry", there

are three possible explanations for this row of holes: 1. They are

traces of original stitches, which must have indicated an arrow above

his eye (not in it). 2. Traces of an arrow sewn in by a later "inspired"

restorer, that were subsequently removed by that person or someone

else, or 3. Traces of an unrelated repair. Bernstein pretty much

discards the third possibility. But what of #2?

I

recently learned about evidence that gives credence to the third

theory, but only a close-up view will enlighten: a row of holes next to

the second figure's eye, that looks suspiciously like stitches that have

been removed! An arrow? If so, then clearly this is the same figure as the other. As historian David Bernstein tells us in a thoroughly investigated "The Blinding of Harold and the Meaning of the Bayeux Tapestry", there

are three possible explanations for this row of holes: 1. They are

traces of original stitches, which must have indicated an arrow above

his eye (not in it). 2. Traces of an arrow sewn in by a later "inspired"

restorer, that were subsequently removed by that person or someone

else, or 3. Traces of an unrelated repair. Bernstein pretty much

discards the third possibility. But what of #2? I

should have realized that the Bayeux Tapestry was subjected to a few

major restorations during its 900+ year-old existence. From what I can

gather, it was restored in 1730, 1818, 1842 and most recently in 1982.

It is recorded that the Victorian-era restorations are fairly easy to

determine because the wool used for the embroidery left stains on the

edges of the holes. But how many figures were altered considerably

beyond their original form? And does Harold's death scene count among

the alterations?

I

should have realized that the Bayeux Tapestry was subjected to a few

major restorations during its 900+ year-old existence. From what I can

gather, it was restored in 1730, 1818, 1842 and most recently in 1982.

It is recorded that the Victorian-era restorations are fairly easy to

determine because the wool used for the embroidery left stains on the

edges of the holes. But how many figures were altered considerably

beyond their original form? And does Harold's death scene count among

the alterations?Sketches drawn by Antoine Benoît before the 18th century restoration do not indicate the row of holes next to the prone Harold's eye, so it is apparent they might have been added later.

Bernstein tantalizingly reassured us in his manuscript that the 1982 restoration was bound to enlighten us through scientific analysis, but so far I haven't been able to find the results of this event. Meanwhile, he gave us a theory as to why the Tapestry shows an arrow in the eye when not one of the six contemporary accounts mention it at all. He theorized that the arrow represented the hand of God in retribution for Harold's oath-breaking. After all, the Tapestry was a Norman creation (propaganda tool?) and it is possible that William saw this supernatural intervention as an expression of God's approval.

Friday, January 9, 2015

Why was King Edward called the Confessor?

Edward the Confessor is the only King of England to be canonized,

though I think many would see him as an unlikely saint. Just for the

record, up until the 4th century a Confessor was seen as a holy person

who was tortured and suffered for his faith but not killed, as opposed

to martyrs who were killed for their faith. After that, since

persecutions had mostly ceased, a Confessor was a holy person who by

virtue of his writings and preachings became an object of veneration. In

reality, it seems that Edward’s canonization was more politically

driven, as Osbert of Clare, the prior of Westminster Abbey started a

campaign in the 12th century to increase the importance (and wealth) of

the Abbey. It took 20 some-odd years, a new Pope and a new King of

England (Henry II) to finally canonize Edward in 1161. Ironically, his

Feast Day is Oct. 13, the day before the Battle of Hastings anniversary

(actually, it had nothing to do with Hastings. That was the day he was

translated-moved to his new tomb-by St. Thomas of Canterbury in Henry

II’s presence).

What made Edward so holy? Well, it is conjectured that his widow Editha commissioned the Life of King Edward (Vita Ædwardi Regis) partly to glorify the deeds of her family, partly to glorify her husband, and partly to excuse her lack of children. After all, if Edward was considered a holy man who was not interested in the things of this world, his sanctity would include refraining from the marriage bed; she couldn’t be held responsible for England’s fate. Nonetheless, this was our most important source for his life and cast him in a holy light. According to Catholic.org, “By 1138, he (Osbert) had converted the Vita Ædwardi…into a conventional saint’s life.”

Here is a legend I found on the Westminster Abbey website: “Edward was riding by a church in Essex and an old man asked for alms. As the king had no money to give he drew a large ring off his finger and gave this to the beggar. A few years later two pilgrims were traveling in the Holy Land and became stranded. They were helped by an old man and when he knew they came from England he told them he was St John the Evangelist and asked them to return the ring to Edward telling him that in six months he would join him in heaven.” When his uncorrupted body was translated in 1163 the ring was removed and placed with the Abbey relics, which of course were plundered in 1540 when the monastery was dissolved. Edward’s body was moved to some obscure place, but Mary Tudor had it returned in 1557 and replaced the stolen jewels with new ones.

Edward was considered one of the Patron Saints of England until Edward III created the Order of the Garter and promoted St. George in his place, although he has remained the patron saint of the English royal family. He is the first English King to cure people suffering from scrofula, “the king’s evil” by the touch of his hand; William of Malmesbury stated that he was already known for this in Normandy while an exile. Interestingly, he is also the patron saint of difficult marriages and separated spouses.

Many would see his ungracious treatment of Earl Godwine in 1051, not to mention his insistence that Godwine wreak havoc with the unfortunate citizens of Dover, as unsaintly behavior. But in the end, his ardor in building Westminster Cathedral seems to have overcome any earlier indiscretions.

What made Edward so holy? Well, it is conjectured that his widow Editha commissioned the Life of King Edward (Vita Ædwardi Regis) partly to glorify the deeds of her family, partly to glorify her husband, and partly to excuse her lack of children. After all, if Edward was considered a holy man who was not interested in the things of this world, his sanctity would include refraining from the marriage bed; she couldn’t be held responsible for England’s fate. Nonetheless, this was our most important source for his life and cast him in a holy light. According to Catholic.org, “By 1138, he (Osbert) had converted the Vita Ædwardi…into a conventional saint’s life.”

Here is a legend I found on the Westminster Abbey website: “Edward was riding by a church in Essex and an old man asked for alms. As the king had no money to give he drew a large ring off his finger and gave this to the beggar. A few years later two pilgrims were traveling in the Holy Land and became stranded. They were helped by an old man and when he knew they came from England he told them he was St John the Evangelist and asked them to return the ring to Edward telling him that in six months he would join him in heaven.” When his uncorrupted body was translated in 1163 the ring was removed and placed with the Abbey relics, which of course were plundered in 1540 when the monastery was dissolved. Edward’s body was moved to some obscure place, but Mary Tudor had it returned in 1557 and replaced the stolen jewels with new ones.

Edward was considered one of the Patron Saints of England until Edward III created the Order of the Garter and promoted St. George in his place, although he has remained the patron saint of the English royal family. He is the first English King to cure people suffering from scrofula, “the king’s evil” by the touch of his hand; William of Malmesbury stated that he was already known for this in Normandy while an exile. Interestingly, he is also the patron saint of difficult marriages and separated spouses.

Many would see his ungracious treatment of Earl Godwine in 1051, not to mention his insistence that Godwine wreak havoc with the unfortunate citizens of Dover, as unsaintly behavior. But in the end, his ardor in building Westminster Cathedral seems to have overcome any earlier indiscretions.

Thursday, July 31, 2014

Duncan was not killed in his bed by Macbeth

Shakespeare told some great stories, but historians will agree that real history often gets buried beneath the great Bard’s verses. The death of King Duncan was one of those exaggerations. For anybody who hasn’t read or seen Macbeth, in essence he meets three witches on the heath who plant the suggestion in his mind that he will be king. The best way to achieve this is to treacherously kill King Duncan in his bed (as Lady Macbeth goads him on), put the blame elsewhere and seize the throne. Righteous countrymen attack his castle in the end and restore the throne to Duncan’s heir.

Just for the record, when king Malcolm II died in 1034 at age 80, there were many claimants to the throne. Duncan’s claim was from Malcolm II through his mother’s side (the first of three daughters). Thorfinn of Orkney, the great Viking warrior, was Malcolm’s grandson through the third daughter, and was raised under the protection of the King. Malcolm eventually made him Earl of Caithness (the first time the title of Earl was used in Scotland); this could have been a consolation prize. Macbeth had a claim to the throne through his wife Grouch, who was considered the real heir based on the customary Tanist succession practiced in Scotland; her father’s claim had been put aside by Malcolm II in favor of Duncan.

So Malcolm II had cleared the way for his favorite grandson, although the 33 year-old Duncan did little to recommend himself to his contemporaries. He fought five wars in five years and lost them all. Ultimately, he made the mistake of trying to claim Caithness which was rightfully ruled by his cousin Thorfinn. This led to a sea battle where Duncan’s forces were ignominiously thrashed, and the king was forced to flee.

That same year in August, Duncan raised an army including many Irish mercenaries, and met either Thorfinn or Macbeth (or both) in the Battle of Burghead on the Moray Firth. This could be same battle I found reference to stating that Macbeth killed Duncan at Pitgaveny, which was nearby. It was also recorded elsewhere that Duncan was killed by his own men immediately after the battle. Regardless of who actually killed him, it is clear that Duncan met his end on the battlefield rather than treacherously in bed. Macbeth was properly elected high king by a council of Scottish leaders, apparently without dissent. In fact, Macbeth ruled for 14 years. This is a far cry from the grasping, tortured protagonist of Shakespeare’s dark tragedy.

Just for the record, when king Malcolm II died in 1034 at age 80, there were many claimants to the throne. Duncan’s claim was from Malcolm II through his mother’s side (the first of three daughters). Thorfinn of Orkney, the great Viking warrior, was Malcolm’s grandson through the third daughter, and was raised under the protection of the King. Malcolm eventually made him Earl of Caithness (the first time the title of Earl was used in Scotland); this could have been a consolation prize. Macbeth had a claim to the throne through his wife Grouch, who was considered the real heir based on the customary Tanist succession practiced in Scotland; her father’s claim had been put aside by Malcolm II in favor of Duncan.

So Malcolm II had cleared the way for his favorite grandson, although the 33 year-old Duncan did little to recommend himself to his contemporaries. He fought five wars in five years and lost them all. Ultimately, he made the mistake of trying to claim Caithness which was rightfully ruled by his cousin Thorfinn. This led to a sea battle where Duncan’s forces were ignominiously thrashed, and the king was forced to flee.

That same year in August, Duncan raised an army including many Irish mercenaries, and met either Thorfinn or Macbeth (or both) in the Battle of Burghead on the Moray Firth. This could be same battle I found reference to stating that Macbeth killed Duncan at Pitgaveny, which was nearby. It was also recorded elsewhere that Duncan was killed by his own men immediately after the battle. Regardless of who actually killed him, it is clear that Duncan met his end on the battlefield rather than treacherously in bed. Macbeth was properly elected high king by a council of Scottish leaders, apparently without dissent. In fact, Macbeth ruled for 14 years. This is a far cry from the grasping, tortured protagonist of Shakespeare’s dark tragedy.

Wednesday, July 2, 2014

Death of Alfred Aetheling

When Queen Emma (widow of Aethelred the Unready) married Canute around 1017, they agreed that the sons from their own marriage would take precedence over any previous children. Things didn’t entirely work out that way, but for the duration of Canute’s reign, her first two sons, Edward and Alfred, remained exiles in her native Normandy.

The second son Alfred’s story is a pitiful one, though it has come down to us full of contradictions. The part we are certain of tells us that during the reign of Harold Harefoot, while Emma lived at Winchester, Alfred landed on the Kentish coast with a band of followers. On orders of the King he was seized, his followers either killed or sold into slavery, and Alfred had his eyes put out, soon dying of his wounds. What we don’t know was why he came to England in the first place, and who exactly was responsible for the dastardly deed, looked upon by disgust even by the Anglo-Saxons hardened to such violence.

One of the rumors was that Emma, discouraged by the non-appearance of Harthacnut, sent a letter to Edward and Alfred encouraging them to invade England and claim the crown. Others conjectured they were testing invasion plans on their own volition. Some say King Harold forged a letter in their mother’s name, intending to lure them to their deaths. Still others said that her sons were simply paying her a visit.

It was said that Edward landed with 40 ships at Southampton and Alfred landed at Dover; the Norman account numbered Alfred’s followers at 600, though other accounts said he came with less than a dozen friends. It has even been stated that Edward fought a battle and defeated the English with great slaughter (considering Edward’s later peaceable reign, I tend to doubt this). However, on hearing of Alfred’s fate, Edward made a hasty retreat back to the safety of Normandy.

It seems relatively certain that Alfred’s capture came as a surprise, and Earl Godwine of Wessex has invariably been linked with his arrest. It is alleged that Godwine wined and dined Alfred, lodged his men throughout the town, then in the middle of the night, either Godwine’s men or Harold’s men raided the town, capturing, torturing and killing the Aetheling’s companions. Whether Godwine followed direct orders from King Harold or whether he acted on his own recognizance is total conjecture. Or he simply might have stepped aside and refrained from interfering with the King’s business.

Did Godwine turn the Aetheling over to Harold’s soldiers, or was he personally responsible for taking Alfred to the island of Ely and blinding him? Nobody really knows, but Godwine was blamed by many of his contemporaries; even though he later cleared himself in court, he was never able to rid himself of the stigma attached to the murder. In any event, the brutal circumstances gave Godwine’s enemies a great deal of ammunition to fling at him. Even at the end of his life, the legend persists that during a feast, Godwine made an oath to Edward that he should choke on a piece of bread if he was responsible for Alfred’s death. Then suddenly, the great Earl was taken with a siezure and collapsed at the table, thus confirming his guilt for all eternity.

The second son Alfred’s story is a pitiful one, though it has come down to us full of contradictions. The part we are certain of tells us that during the reign of Harold Harefoot, while Emma lived at Winchester, Alfred landed on the Kentish coast with a band of followers. On orders of the King he was seized, his followers either killed or sold into slavery, and Alfred had his eyes put out, soon dying of his wounds. What we don’t know was why he came to England in the first place, and who exactly was responsible for the dastardly deed, looked upon by disgust even by the Anglo-Saxons hardened to such violence.

One of the rumors was that Emma, discouraged by the non-appearance of Harthacnut, sent a letter to Edward and Alfred encouraging them to invade England and claim the crown. Others conjectured they were testing invasion plans on their own volition. Some say King Harold forged a letter in their mother’s name, intending to lure them to their deaths. Still others said that her sons were simply paying her a visit.

It was said that Edward landed with 40 ships at Southampton and Alfred landed at Dover; the Norman account numbered Alfred’s followers at 600, though other accounts said he came with less than a dozen friends. It has even been stated that Edward fought a battle and defeated the English with great slaughter (considering Edward’s later peaceable reign, I tend to doubt this). However, on hearing of Alfred’s fate, Edward made a hasty retreat back to the safety of Normandy.

It seems relatively certain that Alfred’s capture came as a surprise, and Earl Godwine of Wessex has invariably been linked with his arrest. It is alleged that Godwine wined and dined Alfred, lodged his men throughout the town, then in the middle of the night, either Godwine’s men or Harold’s men raided the town, capturing, torturing and killing the Aetheling’s companions. Whether Godwine followed direct orders from King Harold or whether he acted on his own recognizance is total conjecture. Or he simply might have stepped aside and refrained from interfering with the King’s business.

Did Godwine turn the Aetheling over to Harold’s soldiers, or was he personally responsible for taking Alfred to the island of Ely and blinding him? Nobody really knows, but Godwine was blamed by many of his contemporaries; even though he later cleared himself in court, he was never able to rid himself of the stigma attached to the murder. In any event, the brutal circumstances gave Godwine’s enemies a great deal of ammunition to fling at him. Even at the end of his life, the legend persists that during a feast, Godwine made an oath to Edward that he should choke on a piece of bread if he was responsible for Alfred’s death. Then suddenly, the great Earl was taken with a siezure and collapsed at the table, thus confirming his guilt for all eternity.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)