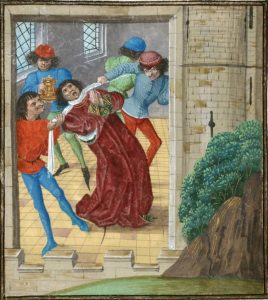

The Lords Appellant Before the King Source: Wikimedia

Thomas was the youngest of all thirteen known children; there were seven years between him and the next older sibling. So by the time he came along, he must have been a surprise! He was fourteen years old when his mother died. Because of his late arrival, it would be safe to say that pretty much all the income-producing royal possessions had been divvied out between his elder brothers. He was predominately reliant upon the exchequer for his annuities—when the money was available, that is. It wasn’t until he married the wealthy heiress Eleanor de Bohun that he acquired some property: the great Castle of Pleshey. So it wouldn’t be a huge stretch to say this may have contributed toward his irascibility.

Even his prospects through marriage were upset. His wife was co-heiress of her great fortune; why not pressure her younger sister Mary into joining a convent, in which case the whole fortune would default to Eleanor? Alas for Thomas, his older brother John had other ideas. Waiting until Thomas was on the continent serving the king, Gaunt concocted a plot with Mary’s aunt to spirit the girl away and marry her to his own son, Henry of Bolingbroke. Finding his plans in ruins, Thomas was hard put to forgive his older brother for cheating him.

Thomas was created Earl of Buckingham at Richard II’s coronation. He had little use for his royal nephew who was only ten at the time, and he always treated the lad with scorn. Even when Richard made him Duke of Gloucester in 1385 (along with his brother Edmund, who was made Duke of York), relations did not improve between them. The following year, when John of Gaunt sailed to Spain to claim his crown of Castile, the main impediment to Gloucester’s ambition was removed. The road was clear to put his nephew in his place and get some control over his troublesome favorites—as he saw it. First, it was time to impeach the chancellor Michael de la Pole, then he and his allies would force the young king to submit to a Great and Continual Council who would implement necessary reforms.

Needless to say, Richard was incensed, though he conceded when Gloucester threatened him with usurpation like his great-grandfather Edward II. The king’s solution was to absent himself from London and travel around the country trying to drum up support. At the same time he had the clever idea to consult with eminent judges and determine whether Gloucester’s actions were treasonous. Under pressure, they agreed. In the end, this gave Richard’s enemies enough ammunition to denounce his evil advisors (they couldn’t go after the king directly) during the Merciless Parliament. Gloucester was the principal mover; he was one of five Lords Appellant, as they were called, who managed to kill or eliminate all of Richard’s friends and allies. I wrote about this at length in my novel, A KING UNDER SIEGE:

But the Lords Appellant weren’t really interested in running the country. Once they had their revenge against the king’s supporters, they quickly lost interest and failed to pursue their advantage, leaving their (illegal) Continual Council in charge. Almost exactly a year later, the king summoned a Great Council and reminded them that he had reached his majority. He declared that he was in charge now, and that the chancellor, Gloucester, Arundel, and Warwick were relieved of their duty, thank you very much. It was as simple as that!

For the next seven years, thing went pretty smoothly. The country was prosperous, there were no major disturbances, and Gloucester kept a fairly low profile, seemingly content to annoy the king on occasion just to stay in practice. But something was apparently going on behind the scenes, though historians are far from certain exactly what happened. Nonetheless, in early 1397 Richard began to suspect the Appellants were stirring up trouble again—and his natural paranoia took over, with dire consequences. Without warning, he decided to take his long-delayed revenge on his enemies, arresting Gloucester, the Earl of Arundel and the Earl of Warwick. They were to be tried by Parliament and declared traitors. The other two Appellants—Henry Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray—were off the hook, for the moment. Bolingbroke was protected by his father, and Mowbray had managed to worm himself back into Richard’s good graces.

Gloucester provided a bit of a dilemma. After all, he was John of Gaunt’s younger brother, and Richard knew it would be next to impossible to get a condemnation from the Duke of Lancaster. While deciding what to do, he sent Gloucester across the Channel to Calais, where he was safely out of sight. Mowbray, who was Captain of Calais, was sent as his jailer. It was all very cleverly arranged; Gloucester was persuaded to write his confession, and when it came his time to appear in Parliament, Mowbray declared that he had died in prison.

Did it look sufficiently suspicious? I’m sure it did, but Richard got away with it anyway—at least, until his usurpation. During Henry IV’s first Parliament, the truth came out and everybody learned that the Duke of Gloucester had been murdered. The only witness who told the story was immediately hustled to his execution, though he claimed he was only guarding the door. Someone had to pay!

All of this is described at length in THE KING’S RETRIBUTION. If Richard hadn’t sent Bolingbroke into exile and appropriated his inheritance, he might have really gotten away with the whole irregular coup. There wasn’t a tremendous outcry at the time; the condemned Lords Appellant had been out of the public eye for many years. Gloucester still managed to stir up trouble, but for the most part he was yesterday’s news. It seemed that nobody gave him much thought except for Richard, who was so traumatized that he just couldn’t let go. In the end, Gloucester’s fate became a rallying cry for Bolingbroke’s rebellion, and the duke’s long shadow overtook his nemesis.

No comments:

Post a Comment